Power & Control in the Golf Swing – A Matter of Balance

Our golf swings — and our attitude toward them — are often a reflection of who we are at our core. Much of our motivation comes from a deep-seated need for control, and the golf swing is no exception. Add in our desire to be powerful, and you have the foundation of how most golfers approach the game. Together it forms our relationship to power & control in the golf swing.

Without having done a formal study, I’d say that 90% of my students come in with a need for control so strong that it actively hinders their motion.

This is important because it directly affects how — and if — we can produce power.

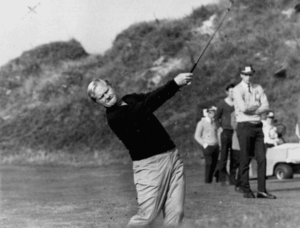

Remember Jack Nicklaus’ upbringing: power first, control second. That idea didn’t come from thin air.

Relationship – Power & Control in the Golf Swing

What determines whether a golf shot flies straight down the fairway or ends up deep in the woods?

It all comes down to impact — the mechanical properties of the strike. In TrackMan terms, we’re talking about face angle and face-to-path. That’s really it. Is your clubface aligned with your path, and is that path roughly aimed toward the target?

For simplicity’s sake, let’s focus on face angle here to make the point about control.

Now, what determines power in the golf swing?

It’s about how much centrifugal force you can unleash into the club — how much the clubhead accelerates in relation to that force. This is influenced by a range of power inputs: the size of the downswing arc, the braking mechanism, rotational forces in both the shaft and body, ground pressure, and more. (The list could go on forever.)

To simplify, let’s focus on just one thing:

How much centrifugal force have you created, and how much speed does it deliver?

So, we have two key factors forming a relationship:

Face alignment and centrifugal force.

Get your face angle reasonably straight and your power unleashed at a consistent level — congratulations, you’re a great golfer. My estimate? Maybe 10% of players manage to do this. The rest have a skewed relationship between the two.

And here’s the thing: focusing on power over control has its advantages — but you can absolutely have both.

Power Only Approach – Benefits & Shortcomings

If you’re someone who just unleashes power and gives very little thought to control, you’re actually not far off.

Being able to produce power — for instance, by using the swing arc as your main driver — not only creates a more advantageous downswing path, it also tends to inspire a natural, momentum-fueled follow through.

That kind of motion makes your body move athletically. You’ve got a living, breathing, reacting swing — and that’s a good thing.

The only problem? You probably lose 2–4 golf balls per round and shoot 78–82 instead of par. You’re likely the one hitting the longest drive in your group, but you still walk off the course feeling like there’s untapped potential.

From a technical standpoint (and speaking from old-school fundamentals, which I personally prefer), you’ve managed to rotate the club in the backswing and re-rotate the shaft in the downswing — both huge stimulators of centrifugal force. And when that force is unleashed, your body naturally reacts and organizes around it.

However, there’s a good chance your wrists, forearms, and upper arms (humerus bones) are working in slightly disadvantageous ways through impact. Most powerful but inconsistent players aren’t thinking about mechanics — they’re just playing golf. And to be honest, I’ll always lean power first rather than the opposite extreme you’ll read about next.

Control Only Approach – Shortcomings & Benefits

Loads of students come in hitting a 7-iron that carries 140 yards with a fairly tight dispersion. They move a bit mechanically, and they all share the same problem — the 5-iron doesn’t go proportionally farther, and the driver isn’t anything to write home about.

This is, more often than not, the profile of a golfer with a big need for control. Somewhere in their development, they chose control over power — probably because it felt safer and kept the ball in play. After all, golf is a game of misses, right?

Most modern instruction lives right here. You close the clubface (compared to old-school fundamentals), then use your arms to shallow the club in the downswing while maintaining lag.

The problem? When you reduce the amount of blade rotation through impact, you also reduce your access to free centrifugal force — the lifeblood of effortless power. I’ve seen it a thousand times.

Impact gets managed with a trail wrist held in flexion, releasing only after the ball. The follow-through arc shrinks, and the swing loses its natural flow.

To add power back in, the student now has two options:

- Intentionally rotate the body through impact.

- Combine that rotation with right-side bend to counter the steepening effect of rotation.

There’s nothing wrong with this approach — it just demands high-level body awareness and puts you in taxing positions. Most golfers from the “control corner” of the power-and-control relationship can’t sustain it.

They end up stuck with a control-based golf swing that’s difficult to perform and hard to repeat.

Personally, I’d rather be a power-first player who loses a couple of balls per round but enjoys the motion. But here’s the key question — can’t you have both?

Control First and Power Second – Disadvantages

When you chase control, you’re often plagued by the illusion that the clubface can stay square for a long time through impact.

Allow me to explain. All great players have clubface rotation. Even the most “stable” hitters rotate the face through impact — it’s just physics. Sure, in theory, you could have zero degrees of rotation, but in practice, it almost never works.

Here’s the point:

The moment you limit rotation, you limit your centrifugal force outlet.

And when that happens, you’re forced to search for power elsewhere — often through hard-to-achieve mechanisms like a “sling-style” body power move. (If you haven’t already, watch my video on power styles — it’ll make perfect sense.)

Long story short: it’s far more difficult to add power from a controlled state than it is to add control to a powerful one.

Let’s unpack that next.

Power First and Control Second – Advantages

A power-only player typically does something like this:

they open the blade around 45 degrees in the backswing, return it to square (0°) at impact, and then rotate it another 90 degrees in the follow-through.

This is the old-school “in-to-out, L-to-L release” — a release that produces tremendous power… and usually costs 2–4 golf balls per round.

A control-only player, on the other hand, might go from 30 degrees open, to square, to 30 degrees closed. The result? Nice contact, but not enough speed or carry to break into single digit handicap.

The best of the best, however, found a third path. They kept that blade rotation in the backswing, squared it at impact, but then limited its rotation through the follow-through.

If we were to average it out, it would look something like this:

45° open → 0° at impact → 45° closed.

Not 90°. Just 45°.

That’s the difference between losing two or three balls per round and losing close to none—while keeping close to all of your power.

So how do you actually achieve this?

You guide the club upward after impact, counteracting the natural rotational forces that want to over-close the face.

The key?

You can only do this if you’ve already created power.

The greats didn’t strangle their golf clubs — they guided them. If you’ve seen me hit balls on YouTube, you’ve probably noticed this in action. My accuracy isn’t an accident — it’s the result of inspiring my swing arc in my favor through the follow-through.

Control – My Own Changed View

I actually made several swing developments just to achieve control. The goal was to have zero club rotation through the impact area while still maintaining power.

Maybe I’m just not as good as some other golfers — but then again, I’m also not not gifted.

It didn’t matter what I did. I could never control it.

And honestly, the pros can’t either. If they could, they’d shoot sub-60 every single round.

Over time, my perception of control has changed completely.

The only thing I can truly do in my motion is to create a flowy, full swing that carries all the way to the follow-through.

When I achieve that — which I do about 19 out of 20 times — I generate enough momentum through the impact area to make squaring the clubface feel almost automatic.

Do I still miss? Sure. All the time.

Do I miss big? Almost never.The benefit of this approach is that it delivers loads of effortless, “free” power — because you finally allow the club to do what it was designed to do.

Suggested Development – Power & Control in the Golf Swing

Allow yourself to open the blade in the backswing and then perform a bunch of downswing drills where you just unleash the club — until you hit big hooks with an inside path.

Awesome. You now have power and good striking properties, but at the same time, your blade control is lousy.

What to do? Focus on the completion of the motion and the follow-through. Make your hands continue their journey through the impact zone in a feeling of acceleration. Don’t worry — the awesome centrifugal force–stimulated braking mechanism between the clubhead and your hands will still be maintained.

Or, you could spend thousands on lessons for the control-first path of golf. Your choice.

In my opinion, the golf swing is massively over-taught. It’s way simpler than you think. If your ambition is to enjoy the game and hit nice shots, you can afford to miss here or there. I miss loads and still hit 13–16 GIR per round on a standard 6600-yard course.

I’ll also say this: control-first isn’t the biggest contributor to a suboptimal golf swing. It’s actually the perception of the motion. Read this article to understand more.

Small sales pitch: Contact me if this is interesting. I provide tools to develop yourself within the fundamentals of old-school golf. The old timers figured this out more than 50 years ago. I’ve spent ten years reviving it in the FMM Swing Academy. It takes 3–5,000 reps and you choose one of three patterns. Click here to go the FMM Swing Academy.

More FMM Project Articles

-

The Swinging Protocol – In the Core of all Great Golfers?

I have a special interest in the golf world, and that is to understand what actually built the best swings of all time. Not just how they look, but what truly built them. What…

-

A Powerful Golf Swing Clips It – Stop Chasing Divots

We are all performing golf swings based on inner images, muscle memory, and athleticism. These different subconscious images will shape how we perform our motion. A powerful golf swing clips it in a shallow,…

-

Perform Your Backswing in Front of Yourself – The Vertical Lift

The backswing might be the most difficult part of golf. Do it right, and while there are no guarantees of a perfect result, do it wrong and you’ve almost certainly ruined your chances of…

General Article Collection Pages

-

All Articles Library – All Creations in One Place

Everything I’ve created over the years. You have different filterings according to the list below. Wish…

-

DIY Swing Change – Advice on How to Successfully Change

Do It Yourself, DIY Swing Change, is what has driven me the last decade in my…

-

FMM Academy – Which Pattern Fits You?

My best live lessons are ten minutes long. Eight minutes of dialogue.5–10 balls struck. Because swing…

-

Golf Swing Styles – Categorization for Context

I categorize golf motion styles into systems for the sake of clarity and understanding. No golfer…

Video Based Articles

-

Low Downswing Hands — 2 Ways Without Letting the Club Fall

Low Downswing Hands – Two Ways Without Letting the Club Fall Many golfers are told that the downswing should begin by simply letting the club fall. For some players that idea works well, but…

-

Shallow Through Impact – Woosnam & O’Grady Release Exit

Shallow Through Impact – Woosnam & O’Grady Release Exit “Shallowing the club” has become one of the most discussed topics in modern golf instruction. Many golfers spend a lot of time trying to shallow…

-

Mechanical vs Athletic Drilling — When the Centipede Fell Down

Mechanical vs Athletic Drilling — When the Centipede Fell Down When the Centipede Fell Down “A centipede was happy quite,Until someone asked which leg goes after which…” The moment it started thinking about mechanics,…

Old School General Articles

-

How Lee Trevino Built One of Golf’s Most Accurate Swings

Most golfers trying to hack the golf swing just ruin it, and some, like Lee Trevino, win six majors. From an accuracy perspective, I would say that his motion is the most efficient I’ve…

-

Why Jack Nicklaus Swing Work – Free of Modern “Rules”

Most people have Ben Hogan as their swing god, and sure, he’s awesome, but my personal favorite will always be Jack Nicklaus Swing. The Golden Bear. It’s the simplicity and effortless feel of it…

-

Ben Hogan 1940s Pre-Accident Swing Change – Power Updated

Nothing in golf quite compares to Ben Hogan’s ball striking induced dominance in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1948 alone he would win 10 titles including 2 majors. The 1940s pre-accident swing rebuild I…